Every working day, Betty Gomez hears stories about human misery. It’s part of the life of a caseworker at Catholic Charities, but Betty takes it in stride, even during times of crises.

One of those times is this summer, as a recent wave of desperate migrants show up at the doorstep of Charities’ headquarters at 1011 First Avenue in Manhattan. They come often after long bus rides from the Texas border that leave them hungry, thirsty, but filled with hope that New York can be a new beginning as it has been for so many before.

Betty finds that Catholic Charities is a place where people can make a direct impact on big problems.

[It’s] like an oasis.

“I happen to love Catholic Charities. Every day coming to work is a happy day,” Betty says. In her four years at Catholic Charities, she has helped clients navigate crises such as Covid, the threat of rental evictions and, now, the migrants coming out of Texas.

“It’s as bad as you can think of,” she says about the experiences of the migrants she deals with, most of whom are from Venezuela, but also including Central Americans and Africans. She hears stories of desperate people trekking through the jungles of Panama, encountering death and criminality, including being robbed of all they have from criminals who prey on the vulnerable.

No crisis is ever the same. And the response is different as well. From her own experience Betty knows what it’s like to be dislocated by events people have no control over.

A Brooklyn native, she worked in education in Puerto Rico and was enjoying retirement in her family’s ancestral home. But Hurricane Maria in 2017 shattered hopes of a restful life.

She returned to New York with her husband, worked through the FEMA bureaucracy to find assistance, and became expert in disaster care management. Now that expertise has been extended.

“It helps,” she says about her encounter with natural disaster. “Everything you learn in life helps you.”

The Venezuelans she counsels are fleeing not natural disasters but manmade catastrophe. Two successive dictatorships have turned up political repression and run the country’s economy into turmoil and scarcity. Hunger is a common problem in a country that was once one of the most prosperous in Latin America.

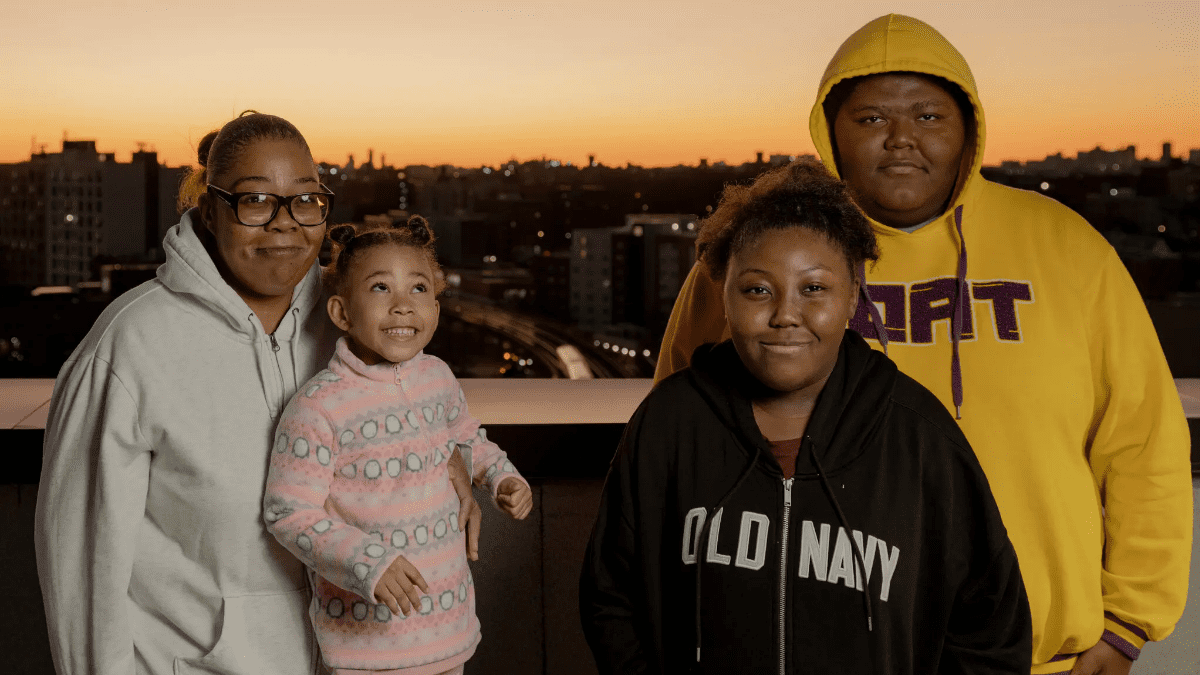

She’s had as many as 19 migrants in a day to review their cases. Each one is treated as an individual. Many are single men, without their families, and they are quite willing to discuss the obstacles and terror they have experienced. The women with children tend to be more reticent, she says.

Some, particularly the men, prefer the city’s parks as temporary havens, as the city shelters remain plagued with violence.

Betty speaks to them in Spanish, and hears, in their stories of upwardly striving, echoes of her own family history. Her grandfather came to Brooklyn from Puerto Rico in the 1920s. She learned Spanish at home growing up, but spoke English on the streets as the goal was to become as American as possible.

Some argue that treating migrants with kindness will only bring more. Catholic Charities, says Betty, strives to treat them decently in any case.

“Most come experiencing hunger and thirst,” she says, noting that Catholic Charities has been quick to offer the migrants food and drink. On the sixth-floor offices, children are given small toys and the air conditioning provides a respite from the scorching heat of the city summer.

For the migrants, she says, the scene “is like an oasis.”