Expert Panel Gathered to Discuss the Issues Before City’s Annual HOPE Count of Those Living on the Streets

A Catholic Charities New York-sponsored panel discussion on homelessness on Jan. 24 covered the seemingly intractable problem from the personal to the big picture of possible solutions.

“What should one do when encountering a person living on the streets?”

In a question-and-answer session, an audience participant raised a dilemma familiar to all New Yorkers: What should one do when encountering a person living on the streets?

The answer, said panelists: always recognize the humanity of the person without a home, even if for whatever reason you cannot offer direct assistance.

“They are people who are homeless,” said Msgr. Kevin Sullivan, Executive Director of Catholic Charities of the Archdiocese of New York, cautioning against lumping people into easily-scorned categories and emphasizing the “people” portion of his definition. He suggested that a simple hello and getting to know the names of people who live on the street is a good beginning. “Their humanity is a start,” said Julie Farber, Executive Director of Covenant House New York. Both Msgr. Sullivan and Julie Farber shared insights with Tameca Gathers, a resident of Second Farms, a Catholic Charities-sponsored housing in the Bronx, and Beatriz Diaz Taveras, Executive Director of Catholic Charities Community Services. The discussion, at the Chapel of the Sacred Hearts of Mary and Jesus on 33rd Street, took place before the city’s annual HOPE Count, during which volunteers spend a night counting who is living without shelter with the goal being tracking the extent of homelessness.

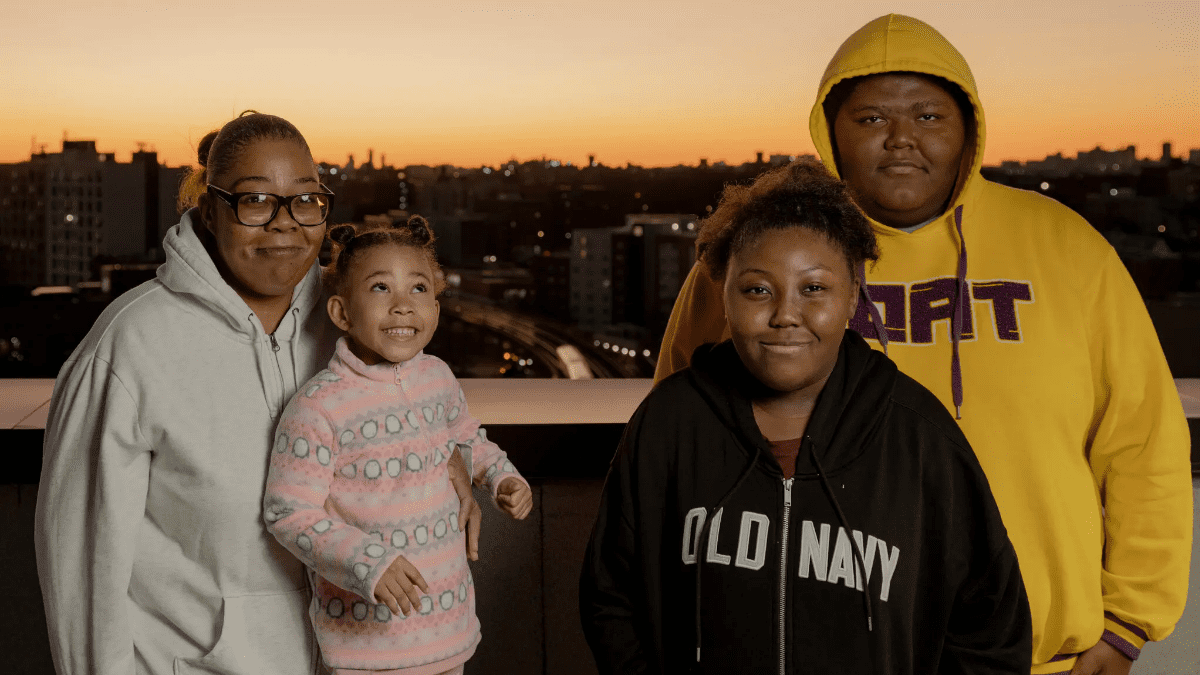

Tameca, whose story is featured in The New York Times through a partnership with Catholic Charities New York, lived in the city shelter system for more than two years after being forced to flee her apartment with her three children, at the time ages 15, 14 and 4.

“I was afraid of someone getting into my information and doing crooked stuff.”

Every night she and the children would return to their room in a city shelter, often bundled with blankets as the heating system failed frequently. She carried her belongings, including important documents, in a backpack, because the family’s valuables would not be secure at the shelter.

“I was afraid of someone getting into my information and doing crooked stuff,” Tameca said.

She would hear from her-then four-year-old who would regularly ask, “Why can’t we go home?” As she earned income from a job, she found that the family was in danger of being kicked out of the shelter for having too much income, even though she was unable to find an affordable apartment in New York’s skyrocketing rental market.

And then Tameca landed in a new home provided by Catholic Charities New York and Catholic Homes at Second Farms in the Bronx last year.

“I went from no heat to having heat,” she said about her move to Second Farms to a gleaming new apartment, complete with a refrigerator for the exclusive use of the family, a luxury for anyone coming from a shelter.

Reasons for homelessness vary, the panelists said. Tameca said her problems emerged after falling in love with the wrong partner. Msgr. Sullivan noted that fleeing domestic violence, not having enough money to pay the rent, being hit by health woes, and the lack of stability in family structures all contribute to homelessness.

Catholic Charities and its affiliated agencies are tackling the issue with a multi-faceted approach, said the panelists.

Julie Farber noted that Covenant House, part of the Catholic Charities New York Federation of Agencies, has always focused on youth, ages 16-24, who come to the agency located near the Port Authority Bus Terminal after escaping bleak family situations.

They are often victims of domestic abuse. Some have been sex trafficked. Another group is rejected by their families for being LGBTQ+. Nearly all have been traumatized in one way or another.

“Catholic Charities assists families who are in danger of losing their homes.”

In response, Covenant House does more than provide simple shelter, said Julie. Mental health care, including individual and group therapy, is a vital part of the program.

Beatriz Diaz Taveras said that Catholic Charities Community Services often assists families who are in danger of losing their homes. Working New Yorkers getting by on low wages can easily find themselves in catastrophic circumstances, such as paying the funeral costs incurred by the death of a loved one and not having enough left over to pay the rent. Job losses can also throw families into turmoil if they are living paycheck-to-paycheck, she said.

“Recovery is possible.”

Sometimes assistance can be as simple as providing job resume advice, showing a struggling breadwinner how their skills can be transferred to higher-paying work, said Beatriz. Other times it can be financial counseling, done in a non-judgmental way, taking into account what people with low-income think their needs are and learning to develop a budget.

She said that through programs such as Beacon of Hope in the Bronx, Catholic Charities is also assisting the mentally ill, many of whom come for help after experiencing homelessness.

Their motto, she said, is “Recovery is possible.”

The needs vary. Some require 24/7 congregant care after being released from mental health facilities, often earlier than they are ready, said Beatriz. Others are placed in their own apartments and are carefully monitored to assure that they continue to make their mental health appointments and keep to a medication schedule. Still others are able to live on their own, with relatively small support interventions.

“Unfortunately, there are not enough beds,” said Beatriz Taveras, noting that Catholic Charities is asking New York State to increase funding support for the mentally ill.

“Catholic Charities plans to develop more low-income housing, more than 1,000 units.”

Msgr. Sullivan noted that Catholic Charities has plans to develop more low-income housing, including more than 1,000 units over the next five years, modeled on the success of Second Farms. And it continues to assist the city in providing support for the more than 40,000 newly-arrived immigrants, most from Central and South America, that came to New York last year after making it to the southern border of the United States. Julie Farber noted that about 30 young migrant adults arrive at Covenant House every night, and the agency is paying for many of the expenses of sheltering them and providing legal assistance.

“They need to be able to work and get housing. There are a lot of challenges,” she said, among them the need for more bilingual staff. On a wider scale, she said, the city needs more affordable housing, the biggest gap seen in the social safety net in a city and state that guarantees basic support for everyone.

“The solution is affordable housing. Shelter is intended to be temporary. It is not intended to be for years. You should not have children growing up in shelters,” she said.

I count Catholic Charities as my family.

Tameca, for one, is glad to have made it out of a shelter system that threatened to warehouse herself and her family for years. She couldn’t have done it without the help of Catholic Charities, she said.

“I count Catholic Charities as my family. They accepted me with open arms. They didn’t judge me or criticize me. They just listened,” said Tameca.

![Cardinal Dolan Shows Support for Immigrants[VIDEO]](https://catholiccharitiesny.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/01/Website-Ratio-1.jpg)